For our project glossary we have adopted a magpie mode. The glossary is a collection of concepts, insights, and provocations that reflect the diverse types of knowledge that our project values. It includes academic scholarship, the best practice of other labs and groups and organisations, our own reflections (and those of our partners) on our work in progress. The glossary is our conceptual toolkit, where we find, define and document the ideas that underpin what we do, but it is also a space for thought, where we reflect on what we’re reading, what’s happening in the lab, and how our work relates to that of others. It is strategically playful, experimental and unfinished. We hope that you will continue to visit the Glossary as it evolves.

Title terms

Living

‘What are you made of? Look at your hands. Draw one palm across the other. Feel the density of your tissues, the bones, musculature, and sinuous ligaments. What gives your tissues substance and form? You have probably been told that your body is composed of trillions of living cells. But what are your cells made of? What is the stuff of life?’ (Natasha Myers, Rendering Life Molecular, 9)

‘[T]here remains no broadly accepted definition of ‘life’ (Chyba and McDonald, 1995). The scientific literature is filled with suggestions; three decades ago Sagan (1970) catalogued physiological, metabolic, biochemical, genetic, and thermodynamic definitions, and there have been many other attempts […] all of which seem to face problems, often in the form of robust counter-examples.’ (Carol Cleland and Christopher Chyba, ‘Defining “Life”’, 388)

‘Living entities can be viewed as bounded, informed autocatalytic cycles feeding off matter/energy gradients, exhibiting agency, capable of growth, reproduction, and evolution.’ (Bruce Weber, ‘What is Life?’, 221)

‘A stone is, in its own way, a living thing, not a biological being but one with a history far beyond our capacity to understand or even imagine.’ (Louise Erdrich, ‘The Stone’, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/09/09/the-stone)

Bodies

‘The term “the body” disregards the full range of bodily differences in favor of prioritizing typicality, standardization, and predictability. In so doing, it aspires toward an inaccessible world, designed for the typical and disregarding the different.’ (Gordon Hall, ‘Why I Don’t Talk about the Body’, 97)

‘As a living entity, the body is vital and chaotic, possessing complexity in equal share to that claimed today by critical and cultural theorists for linguistic systems. The association of the body with human mortality and fragility, however, forces a general distrust of the knowledge embodied in it. It is easier to imagine the body as a garment, vehicle, or burden than as a complex system that defines our humanity, any knowledge that we might possess, and our individual and collective futures.’ (Tobin Siebers, Disability Theory, 26)

‘Bodies are not objects with inherent boundaries and properties; they are material-discursive phenomena. “Human” bodies are not inherently different from “nonhuman” ones. What constitutes the “human” (and the “nonhuman”) is not a fixed or pregiven notion, but nor is it a free-floating ideality.’ (Karen Barad, ‘Posthumanist Performativity’, 823)

‘[D]escribing the body as “malleable” or “plastic” has entered common parlance and dictates common-sense ideas of how we understand the human body in late-capitalist consumer societies in the wake of commercial biotechnologies that work to modify the body aesthetically and otherwise.’ (Luna Dolezal, ‘Morphological Freedom and Medicine’, 312)

‘For Derrida and Haraway the body is already a technology: the hand that allows us to count and form digits, and the movements that enable gesture and writing are formed systems that are never any single body’s to own or create.’ (Claire Colebrook, ‘All Life is Artificial Life’, 2)

Objects

‘[T]he focus on the object productively unmoors and destabilizes the subject, rather than simply doing away with it.’ (Antony Hudek, ‘Detours of Objects’, 16)

“[F]or millennia, a two-cycle phenomenon has been at work: humans create objects, which in turn help to shape humans. This ancient evolutionary process has taken a new turn with the invention of intelligent machines. . . . artifacts that seem to manifest human characteristics act as mirrors or ‘second selves’ through which we re-define our image of ourselves” (N. Katherine Hayles, ‘Computing the Human’, 132)

‘[Humanists] see the imposture of treating humans as objects – but what they don’t realize is that it is also an imposture to treat objects as objects.’ (Bruno Latour, What is the Style of Matters of Concern?, 15)

‘Boundaries are drawn by mapping practices; “objects” do not preexist as such. Objects are boundary projects. But boundaries shift from within; boundaries are very tricky. What boundaries provisionally contain remains generative, productive of meanings and bodies. Siting (sighting) boundaries is a risky practice.’ (Donna Haraway, ‘Situated Knowledges’, 595)

‘If we arrive at objects with an expectation of how we will be affected by them, then this affects how they affect us, even in the moment they fail to live up to our expectations. Happiness is an expectation of what follows, where the expectation differentiates between things, whether or not they exist as objects in the present.’ (Sara Ahmed, ‘Happy Objects’, 41)

“Thing-power gestures toward the strange ability of ordinary, man-made items to exceed their status as objects and to manifest traces of independence or aliveness. constituting the outside of our own experience.” (Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter, xvi)

EDI terminology

Diversity

This is a contested term.

Focusing on race, Nisreen Alwan points out that ‘“Diversity” and “inclusion” imply charity from a position of power and superiority. They give the impression that the group who is opening the door to diversify and include others still holds the key. The point of antiracism is that there should not be a key in the first place’ (Nisreen Alwan, ‘Let’s equalise our antiracist language’, https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/07/03/nisreen-alwan-lets-equalise-our-antiracist-language/).

Sara Ahmed argues that in universities, ‘diversity’ agendas ‘can participate in the creation of an idea of the institution that allows racism and inequalities to be overlooked’ (On Being Included, 14). Meanwhile from disability studies, Lennard Davis critiques how ‘diversity agendas are part of neoliberal ideology – market-driven, citizen as consumer’ (The End of Normal, 4) and how they have limitations, often including types of difference that are photogenic or easy to integrate, whilst silently excluding others. Nonetheless, diversity is a meaningful term for advocacy organisations: ‘Fostering diversity by being inclusive of all disabled people as well as their allies’ (York Disability Rights Forum, https://ydrf.org.uk/).

Equality

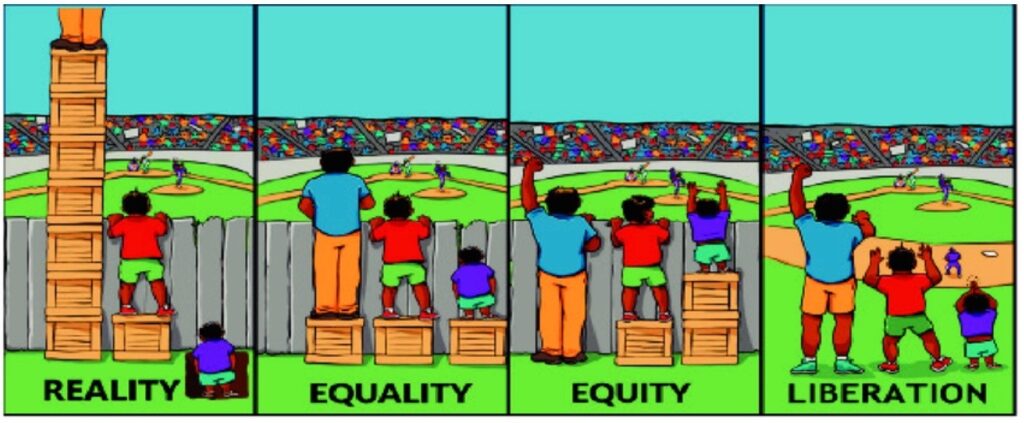

There are lots of visuals to demonstrate the issues with equality vs equity (or justice). This one comes up a lot under Google searches for ‘equality and equity’:

(International Women’s Day, ‘Equality versus Equity’, but also used on multiple other websites)

Equality means everyone being given the same rights, support, opportunities, resources, so it often perpetuates inequalities. This is a well-known critique, so why is it that so many EDI policies still use the term?

Kittay suggests a ‘connection-based equality rather than the individual-based equality more familiar to us. The question for a connection-based equality is not: What rights are due me by virtue of my status as an equal, such that these rights are consistent with those of all other individuals who have the status of an equal? Instead, the question is: What are my responsibilities to others with whom I stand in specific relations and what are the responsibilities of others to me, so that I can be well cared for and have my needs addressed even as I care for and respond to the needs of those who depend on me?’ (Eva Kittay, Love’s Labour, 29)

Inclusion

Like diversity, this is a contested term. It’s often central to institutional frameworks, including our own university’s Equality & Inclusion Vision Statement:

‘As an international, research-intensive university with a strong commitment to student education we will create an inclusive environment that attracts, develops and retains the best students and staff from all backgrounds from across the world and supports them in delivering their ambitions, contributing to our institutional strategic aims’.

(University of Leeds Equality & Inclusion Vision Statement, https://equality.leeds.ac.uk/governance_strategy_policy/equality-and-inclusion-frameworks/e-and-i-framework/)

As Nisreen Alwan argues, ‘inclusion’ reinscribes the power of those doing the including rather than shifting power relationships. She prefers terms such as ‘equity, justice and belonging’ (for more detail see the ‘Diversity’ entry above). Asma Abbas similarly points out that inclusion ‘is so centred on the person who is performing the inclusion that the included can be little more than “beneficiaries”’ (cited in Mitchell and Snyder, The Biopolitics of Disability, 16).

‘Inclusion is a form of diversification, but it can also be violent. Inviting voices into spaces not built for them or that undermine their messages, lived experiences, and expertise can often work against the well-intentioned goals of inclusion. This is what is meant by tokenism or ‘add Indigenous and stir’, where inclusion acts as a sufficient action to deal with underrepresentation, but there is no structural change’ (Max Liboiron, ‘Decolonizing your syllabus?’, https://civiclaboratory.nl/2019/08/12/decolonizing-your-syllabus-you-might-have-missed-some-steps/).

David Mitchell and Sharon Snyder use the term ‘inclusionism’ to describe a neoliberal approach to integration practices that is actually ‘a new formation of tolerance’ (The Biopolitics of Disability, 12). Inclusionism describes ‘an embrace of diversity-based practices by which we include those who look, act, function, and feel different’ (4), which has limitations: ‘Inclusionism requires that disability be tolerated as long as it does not demand an excessive degree of change from relatively inflexible institutions, environments, and norms of belonging’ (14, original emphasis). However, some disability groups would see these critiques as watering down (or even erasing) a word that’s really important to them. (See, for example, The Greater Manchester Coalition of Disabled People’s aim ‘to promote the rights of disabled people and our inclusion in society’.) Working with project partner Blueberry Academy, we experienced firsthand how truly accessible environments can obviate the need for inclusion.

Methodologies

Co-creation

Co-creation is the synergistic process of creating together, where multiple stakeholders, including our project team, partners, and their respective communities contribute collaboratively towards a specific goal, outcome, or product. Rooted in the principles of accessibility and cooperation, our co-creative practice encourages diverse perspectives and values the unique input from all involved parties. This extends to our whole project community of practice, where shared knowledge, skills, and experiences enrich the collective output. A defining characteristic of co-creation is the shared ownership of the results, promoting a sense of collective achievement and shared responsibility. The outcome of co-creation is not just the tangible product, but also a stronger, more engaged community.

It is telling that much of the high-profile discussion around co-creation adopts the language of marketing, commerce, and consumers (see, for example: Ind and Coates, ‘The Meanings of Co-Creation’, 2013; Sarasvuo, Rindell & Kovalchuk, ‘Toward a conceptual understanding of co-creation in branding’, 2022). For us, co-creation is about recognising, appreciating, and integrating different perspectives that can be brought to bear on collective projects and endeavours. It is heavily participatory and extends beyond co-production in that it shapes not just outputs and processes, but the generation of questions and problems, and the defining of project parameters. We also recognise that while co-creation has been used as an effective tool in other areas, such as the generation or refining of policy, our application of co-creation is not mechanistic; we do not seek to have a specific impact, but to enable, facilitate, and create in ways which naturally lead to more collective and shared outcomes and benefits. In this way, we try to go beyond established methods in co-creation, such as observation, identification of ‘potential target groups’ and ‘model characters’, and ‘cooperation’ (Stanford University, ‘Co-Creation & Participatory Research’).

Collaboration

‘We do not use the terms “community outreach” or “public education” in our work because these terms assume something called the “deficit model,” where publics/communities lack knowledge and need to be educated by academics. Instead, we collaborate with, work for, work with, pay, learn from, share skills with, and partner with other groups, all of which are different modes of reciprocal relation that allow value to flow in two directions and on shared terms. They are also more specific terms, which adds transparency to our relations.’ (CLEAR Lab Book, 11)

The ‘deficit model’ is a widely used but much critiqued term in science and knowledge communication. In addition to the assumption that there is a mono-directional movement of knowledge, the other problematic is that it presents non-specialists as malleable, absorbing and “learning” rather than critically reflecting on information (Miller, ‘Scientific Literacy: A Conceptual and Empirical Review’, 1983). Even the term ‘literacy’ implies a process of becoming-expert, rather than recognising that participants in dialogue bring with them diverse forms of expertise. Indeed, ‘dialogue’ is something which characterises mature collaboration, with mutual, equitable exchange (Reincke, Bredenoord and van Mil, ‘From Deficit to Dialogue in Science Communication’, 2020). This recognises that the purpose of collaboration is not to persuade or educate, but to bring together, reflect, and create.

We see collaboration as a fundamental tool: it is not just desirable, but essential. It is also something which functions both within our team – we are all co-collaborators – and beyond it. Effective collaboration requires that we appreciate what everyone brings, their circumstances and contexts, as well as their goals and ambitions. This goes beyond the framing of research collaboration as ‘an effective way to ensure research, providing an opportunity for academics to engage with others affected by and interested in the proposed research’ (ESRC, ‘Our expectations for research collaboration’).

Facilitation

Enhancing our practice of facilitation is critical to our aims of being accessible, enabling, and respectful. It’s relevant to our work with partners, the internal workings of the team, and in the way we engage with ideas, concepts and methods. It is important to recognise that to use facilitation effectively does not require us to be facilitators ourselves (Institute of Cultural Affairs, ‘What is Facilitation?’). Methods of facilitation include a variety of practical exercises, analyses, and processes such as gap analysis, open spaces, and brainstorming (International Association of Facilitators, ‘Session Lab’). While we draw on these techniques for discrete activities and sessions, we also seek to practice integrated facilitation as widely as possible to draw out and provide spaces for a diverse range of voices and perspectives. Facilitation is about catalysing, enabling and cooperating, reflecting the origin of the term itself; it is akin to providing a sense of ease or easement. To practice effective facilitation is to recognise that the process involves different areas of focus, including designing, intervening, recording, monitoring and supporting (Involve, ‘Introduction to Facilitation’).

‘Facilitation is a discussion method that aims to bring collective knowledge together. Rather than styles of discourse characteristic of teaching, leadership, or debate, all of which are more individualistic and based on a single main “knower,” facilitation looks to “grease the wheels” of everyone else’s knowledge. Facilitation addresses how different people in the room are more or less likely to speak, be heard, or be interrupted, and works to address those disparities. Facilitation is not intuitive, though intuition helps. It’s a skill, and it has to be trained.’ (CLEAR Lab Book, 51)

Environments

Academic research culture

Where are we starting from?

Academic research – and lab research in particular – has historically been built on, and has profited from, the exploitation of marginalised bodies and communities. As Jay Dolmage points out, eugenic science in all its forms was driven by universities and research on disabled, Indigenous and Black bodies and minds (Jay Dolmage, Academic Ableism, Intro).

The university has also been a major driver in producing ideas about what constitutes ‘normal’ or ‘desirable’ characteristics of body and mind, and thus in producing and maintaining ableism: ‘academia powerfully mandates able-bodiedness and able-mindedness, as well as other forms of social and communicative hyperability’ (Jay Dolmage, Academic Ableism, 7).

Academic research culture tends to value qualities that centre on ideas of reason and are based on assumptions about able-mindedness: ‘rationality, criticality, presence, participation, productivity, collegiality, security, coherence, truth, and independence’ (Margaret Price, Mad at School, 30). Research culture often excludes other ways of knowing or encountering the world.

Historically, academic research has been shaped around the ‘life of the mind of able-bodied [and we might add neurotypical] white men’ whose work was enabled by ‘the invisible labor of […] women and other marginalized people’ (Bailey, ‘The Ethics of Pace’, 289). It remains the case that ‘white, able-bodied men are still imagined as prototypical scholars’ (Bailey, ‘The Ethics of Pace’, 289).

Academic research culture can have detrimental impacts on health: ‘For researchers, poor research culture is leading to stress, anxiety, mental health problems, strain on personal relationships, and a sense of isolation and loneliness at work’ (Wellcome, What Researchers Think About the Culture They Work In, 3).

Access/accessibility

‘When we examine accessibility through the lens of user experience, we see that accessibility is:

- A core value, not an item on a checklist.

- A shared concern, not a delegated task.

- A creative challenge, not a challenge to creativity.

- An intrinsic quality, not a bolted-on fix.

- About people, not technology.’

(Sarah Lewthwaite, David Sloan and Sarah Horton, ‘A Web for All’, 130)

‘We currently live in a society in which one single disability can be linked to any other disability in a negative way. But could we live in a society in which the accessibility we create for one person can also lead us to broaden and expand accessibility for all? On the way to this world, educators at least have to recognize that physical access is not “enough”—it is not where accessibility should stop.’ (Jay Dolmage, Academic Ableism, 10)

‘What might it mean to welcome the disability to come, to desire it? What might it mean to shape worlds capable of welcoming the disability to come?’ (Robert McRuer, Crip Theory, 207)

Care

‘On the most general level, we suggest that caring be viewed as a species activity that includes everything that we do to maintain, continue, and repair our ‘world’ so that we can live in it as well as possible. That world includes our bodies, ourselves, and our environment, all of which we seek to interweave in a complex, life-sustaining web.’ (Bernice Fisher and Joan Tronto, ‘Toward a Feminist Theory of Care’, 40)

‘care means moving together and being limited together. It means giving more when one has the ability to do so, and accepting help when that is needed. It does not mean knowing exactly what another’s pain feels like, but it does mean respecting each person’s pain as real and important. Finally, care must emerge between subjects considered to be equally valuable (which does not necessarily mean that both are operating from similar places of rationality), and it must be participatory in nature, that is, developed through the desires and needs of all participants’ (Margaret Price, ‘The Bodymind Problem’, 279).

‘[C]are is not only ontologically but politically ambivalent. We learn from feminist approaches that it is not a notion to embrace innocently. Thought and work on care still has to confront the tricky grounds of essentializing women’s experiences and the persistent idea that care refers, or should refer, to a somehow wholesome or unpolluted pleasant ethical realm . . . Delving into feminist work on the topic invites us to become substantially involved with care as a living terrain that seems to need to be constantly reclaimed from idealized meanings, from the constructed evidence that, for instance, associates care with a form of unmediated work of love accomplished by idealized carers’ (Maria Puig de la Bellacasa, Matters of Care 7-8).

‘Care is a selective mode of attention: it circumscribes and cherishes some things, lives, or phenomena as its objects. In the process, it excludes others.’ (Aryn Martin, Natasha Myers and Ana Viseu, ‘The Politics of Care in Technoscience’, 3)

Caring is highly political and politicized. It requires tremendous resources and references to its economic impacts demonstrate the ways in which care is instrumentalised: ‘Caring is such an important part of life. It’s simply part of being human. Carers are holding families together, enabling loved ones to get the most out of life, making an enormous contribution to society and saving the economy billions of pounds.’ (‘About Us’, Carers UK, https://www.carersuk.org/about-us/why-we-re-here)

Crip spacetime

The LivingBodiesObjects project is interested in exploring what academic research culture can learn from disability/crip theory about reorientations to time. Research culture has particular, pressured orientations to time via funding cycles and deadlines, REF timetables, appointment and promotion criteria. It values productivity, overwork (long hours), endurance, intensity, and efficiency (see Price, Mad at School; and Academic Research Culture entry). Can our project help to question and dislodge these unhealthy, unsustainable practices by demonstrating the value of pacing, resting, moving slowly or quickly when needed, and scheduling generously?

In our lab work, how can we be creative with ideas of pace and scheduling on a day-to-day/week-to-week basis? It’s one of the things that is really hard to build into academic work when we all always have time pressures and multiple commitments!

One thing that has become clear over the beginning of the project is how fast research time flies… What seems like a sensible model of time at application stage – 6-month residencies with overlaps – goes so fast in reality. And while overlaps are great for collaborative learning and sharing, it does mean there are no breaks or periods of rest, no moments to breathe in between intense activity. How do we create space for rest and rejuvenation? This isn’t a criticism of the project per se, just an observation about the realities of project work.

For future projects, how might we take what we’ve learnt about time and health and wellbeing from this project (and from all the great work in disability studies) and build it into the project design and schedule more explicitly? Rest breaks, pauses, reflection points, slowness… Can we encourage funders to see why it’s a good idea to fund projects built around health working practices?

Crip spacetime explains ‘what it means to be disabled in specific spaces’ and takes the focus off individual bodies and accommodations, instead ‘focusing instead on relations, systems, objects, and discourses. Essentially, crip spacetime shows that thinking about disability and access in terms of individual bodies not only does an inadequate job of explaining both disability and access but also tends to exacerbate inequity and block efforts at inclusivity.’ (Margaret Price, ‘Time Harms’, 257-258)

‘[T]heories of crip time address how illness, disease, and disability are conceptualized in terms of time, affect one’s experiences of time, and render adherence to normative expectations of time impossible, for example, timeliness, productivity, longevity, and development, or what Elizabeth Freeman (2010) calls “chrononormativity.” But theories of crip time also highlight how people are refusing and resisting those very expectations, thereby creating new affective relations and orientations to time, temporality, and pasts/presents/futures.’ (Alison Kafer, ‘After Crip, Crip Afters’, 428)

Crip time involves a ‘reorientation to time’ that has the potential to offer a ‘challenge to normative and normalizing expectations of pace and scheduling […] crip time bends the clock to meet disabled bodies and minds’ (Alison Kafer, Feminist Queer Crip, 27)

Laboratory

We conceive of our laboratory as antithetical to the extractive and heavily-managed, institutional-serving entities described in many areas of academic literature. For example, Roger Bertholf describes them: ‘A well-designed laboratory service is an asset to the institution it serves, providing timely laboratory results that are used to improve patient care. In addition, prudent choices for equipment and personnel, and attention to designing efficient processes that do not waste time or resources, benefit the institution by producing an essential service at a competitive cost. In some circumstances, a greater investment results in long-term savings.’ (Bertholf, ‘Laboratory Structure and Function’, 1)

Historically, laboratories embody many of the problematic imperial power dynamics which we seek to critique. The term itself implies control, regulation and mastery over phenomena and others; note, for example, Bruno Latour’s classic piece ‘Give me a Laboratory and I will Raise the World’ (1983) in which he argues that laboratories are creative, dynamic space, which can provide a basis for innovation in both science and society.

A desirable and effective laboratory is one not lacking in coherence, not abandoning the ethos of good laboratory practice (GLP), but recognising the limitations associated with propagating hierarchical structures of authority over nature and society. Just as scientific laboratories – which require careful management and regulation to ensure safety – are managed and carefully curated spaces, so too is deep thinking needed about how any collaborative, experimental space is constructed and made real.

Pace and speed

‘We have never experienced such a world where rapidity – speed – is at the very core of our collective and individual experience’. Contemporary social formations are marked by an ‘open-ended form of speed, which means that the rate at which humans communicate and the rates of increase in productivity and efficiency can never be fast enough. In this postmodern economy the rate at which we do things has become the defining factor’ (Robert Hassan, The Empire of Speed, 7–8; 17.)

Media and technology produce ‘a broad condition of immediacy [that establishes] cultural assumptions and expectations of effortlessness, ubiquity and endless delivery in a fast-paced, technologically-replete and telemediated world.’ (John Tomlinson, The Culture of Speed: The Coming of Immediacy, 158)

‘When the pace of life in a society increases, there is a tendency for more people to become disabled, not only because of physically demanding consequences of efforts to go faster, but also because fewer people can meet expectations of “normal” performance; the physical (and mental) limitations of those who cannot meet the new pace become conspicuous and disabling, even though the same limitations were inconspicuous and irrelevant to full participation in the slower-paced society. Increases in the pace of life can be counterbalanced for some people by improvements in accessibility, such as better transportation and easier communication, but for those who must move or think slowly, and for those whose energy is severely limited, expectations of pace can make work, recreational, community, and social activities inaccessible.’ (Susan Wendell, The Rejected Body, 37-38)

Moya Bailey critiques how ‘the academy demands more and more output […]. Efficiency and productivity drive the pace of life, and the ethics of that pace—the demand it makes on the human body—is rarely if ever questioned’ (Bailey, ‘The Ethics of Pace’, 287). She argues that ‘By adopting an ethics of pace in our scholarly practice, […] we can disrupt debilitating patterns in academia and beyond’. In her own work, she argues ‘for a slowed down DH [digital humanities] that values moving at the speed of trust, which requires a more democratized relationship with time. Because DH is already attentive to collaborative scholarship, a slow DH would allow for moments of reflection so that multiple collaborators from different vantage points are valued.’ (Moya Bailey, ‘The Ethics of Pace’, 288). This idea of moving at the speed of trust is so valuable for researchers working collaboratively. In LBO we ask how we might achieve a pace of work that is founded on an awareness of intersectionality and allows trust to develop naturally over time, through meaningful engagement.

Pause

Dave introduced this concept very early on in the pre-residency phase (what he termed the ‘pause before the start’ of the project) and it has really resonated for us as a useful concept since then. Pausing creates a moment to take stock and reflect, to stop doing something if it’s not working or is causing problems, to rethink how we do something from that moment on. It was useful to pause in September 2022 to catch up on the EDI work we wanted to do, but were behind on, and to take time to begin working out the ethics of the residencies. Pausing recognises that we might need to slow down and think about how to proceed when pressures of scheduling, deadlines, workloads often compel us to carry on regardless or make do with what we’re doing and how we’re doing it. Pausing shows that we value something, that we can’t proceed until we’ve got this thing right and we’ll shift our timeframes to get it right. Sometimes we need to pause to rest as well. Thinking of the pause as a strategy we can draw on allows us to think more actively about our energy levels, workloads and capacities.

Spaces of Health

‘If we imagine that disability is something that bodies have or display, then we restrict the meaning of the term to a physiological, medical definition of that impairment. But if we imagine that disability is defined within regimes of pharmaceutical exchange, labor migration, ethnic displacement, epidemiology, genomic research, and trade wars, then the question must be asked differently. Does disability exist in a cell, a body, a building, a race, a DNA molecule, a set of residential schools, a dialysis center, a special education curriculum, a sweatshop, a rural clinic?’ (Michael Davidson, Concerto for the Left Hand, 174)

‘In healthscapes, health and medicine are viewed as far more than particular institutions in their conventional sociological framings, separable from others such as family, religion, economy, polity, media. Instead healthscapes attempt to capture all of these together, however inadequately, in their material, semiotic, and symbolic dimensions (e.g., Hall 1997). Healthscapes are kinds of assemblages (Marcus and Saka 2006), infrastructures of assumptions as well as people, things, places, images.’ (Adele E. Clarke, ‘From the Rise of Medicine to Biomedicalization’, 105-6)

Technology

We understand ‘technology’ as a broad concept that encompasses tools, systems, methods, and devices created and used by humans to navigate, understand, and interact with their environment, as well as to solve problems, enhance abilities, and fulfil personal or social needs and objectives. This includes a wide range of applications, from traditional tools and techniques like yoga and cooking, to advanced innovations such as virtual reality and artificial intelligence and includes the body itself as a tool.

Provocations

By provocation we not only mean attitudes and approaches that are provocative and challenging, but also those that might unsettle and create uncertainty. While disruption and rebellion provoke through active interventions, vulnerability or doubt can be quieter or softer, but no less effective. In their own way, each disturbs critical methods and forces a re-evaluation of how work can be done.

Disruption

I know that there’s a specific disability label here – DisRupt – but it appeals to me for more reasons than this. As the project is progressing, I want to see more disruption – creation as disruption especially – but in fact I’m also increasingly thinking how the ordinary and mundane are disruptive. Everyday moments at Blueberry – coffee breaks, conversations about football – disrupt what I think I know about disability, for example.

‘Disabled artists are often overlooked or excluded from opportunities and projects, limited and patronised by the ableist attitudes imposed on us by our sector and society. DISrupt is here to challenge those harmful stereotypes and make sure that disabled artists aren’t ignored any longer.’ (‘Why we need DISrupt’, DISrupt arts collective manifesto, https://disruptartsleeds.co.uk/)

Doubt

‘There is something generative about doubt; doubt and uncertainty keep the wheels of science and medicine spinning, yet they also make everyone at least a little anxious about what they’re doing. So, there is something dialectical here: physicians, scientists, patients, their families, funding agencies, everyone, really, living between the drive toward certainty, hoping for some kinds of liberation – maybe a cure – in knowing. Yet, they all live in a landscape of ongoing uncertainty, doubt about whether this diagnostic category […] captures what it is intended to capture, wondering if it is sufficient to motivate sensible inquiry’. (Matthew Wolf-Meyer, ‘What Can We Do with Uncertainty?’ http://somatosphere.net/forumpost/what-can-we-do-with-uncertainty/)

Failure

‘Under certain circumstances failing, losing, forgetting, unmaking, undoing, unbecoming, not knowing may in fact offer more creative, more cooperative, more surprising ways of being in the world.’ (Jack Halberstam, The Queer Act of Failure, 2-3)

‘The queer art of failure turns on the impossible, the improbable, the unlikely, and the unremarkable. It quietly loses, and in losing it imagines other goals for life, for love, for art, and for being.’ (Jack Halberstam, The Queer Act of Failure, 88)

Failure is productive; we learn from failure. Nonetheless, it can be difficult to fail in university contexts. The FailSpace project at Leeds is exploring ‘how organisations in the cultural sector can recognise, acknowledge and learn from failure.’ There is an increasing recognition of the positive effects which the embracing of failure, and the potential of failure, can yield for organisations, communities, and interactions. This speaks also to the recognition of failure as an inherent part of research and career. Compiling a “CV of Failure” is a well-established idea, but of course it too is principally used by those within the academy who can “afford” failure; that is, they are insulated from the potentially high-disruptive consequences of failure. However, there is something powerful and positive in recognising that the outward expressions of research – publications, outcomes, impacts, collaborations – are highly reified and don’t recognise the multiple failures which are likely to have occurred in their making.

Feminist Killjoy

‘Does the feminist kill other people’s joy by pointing out moments of sexism? Or does she expose the bad feelings that get hidden, displaced, or negated under the public signs of joy? Does bad feeling enter the room when somebody expresses anger about things, or could anger be the moment when the bad feelings that circulate through objects get brought to the surface in a certain way? Feminist subjects might bring others down not only by talking about unhappy topics such as sexism but by exposing how happiness is sustained by erasing the very signs of not getting along. Feminists do kill joy in a certain sense: they disturb the very fantasy that happiness can be found in certain places. To kill a fantasy can still kill a feeling. It is not just that feminists might not be happily affected by the objects that are supposed to cause happiness but that their failure to be happy is read as sabotaging the happiness of others.’ (Sara Ahmed, The Promise of Happiness, 65-66).

There are other types of killjoys that have emerged during this project: the accessibility killjoy who points out when activities or spaces are not accessible; the ethics or consent killjoy who questions whether or how it’s appropriate to do something. The killjoy is an important role that we value!

Humility

‘In dominant modes of doing research, values of individualism, heroism, machismo, rescue, paternalism, debate, individual genius, and exceptionalism are dominant. Humility counteracts these tendencies. Humility comes from the understanding that our world is interconnected. Being humble means that we—as members of larger groups of humans and others —recognize that we are not singular nor superior in our knowledge, perspective, experience, or social position, and that we are connected to others (whether we want to be or not). We can be humble by being ready to change our minds and actions, being responsive to context, stepping back and listening instead of taking up space, and being mindful of our surroundings so we might adapt to it rather than force it to adapt to us. It is about recognizing that one still has much to learn regardless of age, education, or lived experience and about remaining teachable, no matter how much we already know. A humble person understands that there are many ways to know things, many different forms of knowledge, and recognizes the limits of a single way to know things (e.g.: strictly via the scientific method is not superior to lived experience, but is a different kind of knowledge, or even that your own good intentions are better than the other good intentions in the lab). This all sounds super serious, but a good sense of humour helps humility. […] Humility is not modesty; modesty usually means not talking about or celebrating your achievements. If you are modest, then you are not acknowledging or celebrating the larger group of people and relationships you are part of and how they are crucial to those achievements; you do an injustice to yourself and those relations by practicing modesty (erasure of connections) rather than humility (being beholden to connections). Humility is a verb, not a noun. It is not just discursive work (saying things in support, acknowledging others verbally in Land acknowledgements), but involves concrete actions that make material change on the ground.’ (CLEAR Lab Book, 9-10, https://civiclaboratory.nl/clear-lab-book/)

‘[A]gility can also be humility. Precisely because it’s not entrenched, it can accept the need to pause and doubt, to think about the next move, to plan carefully, sensitivity, ethically. Can’t the ways that Medical Humanities scholarship works across subjects, trying to build complexity, be seen as a desire for a humble intellectual agility in this way? And can’t agility be a word and idea that Disability Studies can claim as, recognising the need for a humility in its approaches, it asserts the worth of people and disabled lives?’ (Stuart Murray, Medical Humanities and Disability Studies, 126)

In/Disciplined

‘I am drawn to this for a number of reasons: First, it allows for an obvious situating within discussions of the disciplinary concerns that necessarily speak of how academic scholarship works in institutional and intellectual spheres; second, it qualifies this location – messes it up –because of its clear suggested unruliness. It places disciplines in recognisable structures but then subjects them to the rule-breaking energy of nonconformity.’ (Stuart Murray, Medical Humanities and Disability Studies, 12)

Rebellion

‘In a position of heroic rebellion, the medical humanities can be said to harness “the intellectual practice of the humanities with all of its democratising energies and dangerous possibilities, which enable and promote fearless questioning of representations, challenges to the abuses of authority and a steadfast refusal to accept as the limits of enquiry the boundaries that medicine sets between biology and culture.” This version of medical humanities is hostile, dogged, sceptical, and separable from the medical practices it seeks to target.’ (Will Viney, Felicity Callard, and Angela Woods, ‘Critical Medical Humanities’, 3-4)

Trouble

‘Our task is to make trouble, to stir up potent response to devasting events, as well as settle troubled waters and rebuild quiet places.’ (Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble, 1)

Uncertainty

‘What if we take uncertainty and put it at the core of our investigatory and change-making practice? […] how might we harness uncertainty, to move forward with it into futures so we are vigilant of our blind [sic] hope for ‘better’ experiences when we are intervening in change? Uncertainty, we argue, brings with it possibilities. It does not close down what might happen yet into predictive untruths, but rather opens up pathways of what might be next and enables us to creatively and imaginatively such worlds with possibilities.’ (Yoko Akama, Sarah Pink and Shanti Sumartojo, Uncertainty and Possibility, 3)

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara, On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012)

Ahmed, Sara, The Promise of Happiness (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010)

Ahmed Sara, ‘Happy Objects’, in The Affect Theory Reader, ed. by Melissa Gregg and Gregory

Seigworth (Durham: Duke UP, 2010), pp. 29-51

Akama, Yoko, Sarah Pink and Shanti Sumartojo, Uncertainty and Possibility: New Approaches to Future Making in Design Anthropology (London: Blomsbury, 2018)

Alwan, Nisreen, ‘Let’s equalise our antiracist language’, BMJ blog, 3 July 2020, https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/07/03/nisreen-alwan-lets-equalise-our-antiracist-language/

Barad, ‘Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to

Matter’, Signs 28.3 (2003), 801-831

Bennett, Jane, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham, NC: Duke University

Press, 2010)

Bertholf, Roger, ‘Laboratory Structure and Function’, in Clinical Core Laboratory Testing, ed. by Ross Molinaro, Christopher McCudden, Marjorie Bonhomme, and Amy Saenger (Boston MA: Springer, 2017), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-7794-6_1

Clarke, Adele E., ‘From the Rise of Medicine to Biomedicalization: U.S. Healthscapes and

Iconography, circa 1890 – Present’, in Biomedicalization: Technoscience, Health, and Illness in the U.S., ed. by Adele E. Clarke, Laura Mamo, Jennifer Ruth Fosket, Jennifer R. Fishman, and Janet K. Shim (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), pp. 104–46

CLEAR (Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research), CLEAR Lab Book: A living manual of our values, guidelines, and protocols, V.03 (St. John’s, NL: Civic Laboratory for Environmental Action Research, Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador, 2021)

Cleland, Carol E. and Christopher F. Chyba, ‘Defining “Life”’, Origins of Life and Evolution of the

Biosphere 32 (2002), 387–393

Claire Colebrook, ‘All Life is Artificial Life’, Textual Practice 33.1 (2019), 1-13

Davidson, Michael, Concerto for the Left Hand: Disability and the Defamiliar Body (Ann Arbor:

University of Michigan Press, 2008)

Davis, Lennard J., The End of Normal: Identity in a Biocultural Era (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2014)

Dolezal, Luna, ‘Morphological Freedom and Medicine: Constructing the Posthuman Body’, in

The Edinburgh Companion to the Critical Medical Humanities, ed. by Sarah Atkinson, Jane

Macnaughton, Jennifer Richards, Anne Whitehead, and Angela Woods (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), pp. 310-324

Dolmage, Jay, Academic Ableism: Disability and Higher Education (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2018)

Erdrich, Louise, ‘The Stone’, The New Yorker, 9 September 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/09/09/the-stone

Greater Manchester Campaign for the Rights of Disabled People, Campaigning for the Rights and Full Inclusion of Disabled People, https://gmcdp.com/

Halberstam, Jack, The Queer Art of Failure (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011)

Hall, Gordon, ‘Why I Don’t Talk about the Body’, Monday Journal, 4 (2020), https://monday-

journal.com/why-i-dont-talk-about-the-body-a-polemic/

Haraway, Donna, ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of

Partial Perspective’, Feminist Studies, 14.3 (1988), 575-599

Haraway, Donna, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham and

London: Duke University Press, 2016)

Hassan, Robert, The Empire of Speed: Time and the Acceleration of Politics and Society (Leiden and Boston, MA: Brill, 2009).

Hayles, N. Katherine, ‘Computing the Human’, Theory, Culture and Society 22.1 (2005), 131– 151

Hudek, Antony, ‘Detours of Objects’ in The Object, ed. by Antony Hudek (London/Cambridge

Mass: Whitechapel Gallery/MIT Press, 2014), pp. 16-17.

International Women’s Day, ‘Equality versus Equity: What’s the Difference as we #EmbraceEquity for IWD 2023 and Beyond?’, https://www.internationalwomensday.com/Missions/18707/Equality-versus-Equity-What-s-the-difference-as-we-EmbraceEquity-for-IWD-2023-and-beyond

Kafer, Alison, Feminist, Queer, Crip (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013)

Kafer, Alison, ‘After Crip, Crip Afters’, South Atlantic Quarterly, 120.2 (2021), 415-34

Kittay, Eva, Love’s Labour: Essays on Women, Equality, and Dependency (London: Routledge,

1999)

Latour, Bruno, What Is the Style of Matters of Concern? (Assen: Van Gorcum, 2008)

Lewthwaite, Sarah, David Sloan and Sarah Horton, ‘A Web for All: A Manifesto for Critical Disability Studies in Accessibility and User Experience Design’, in Manifestos for the Future of Critical Disability Studies, Volume 1, ed. by Katie Ellis, Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, Mike Kent, and Rachel Robertson (Abingdon: Routledge, 2019), pp. 130-41

Liboiron, Max, ‘Decolonizing your Syllabus? You Might Have Missed Some Steps’, CLEAR Lab blog, 12 August 2019, https://civiclaboratory.nl/2019/08/12/decolonizing-your-syllabus-you-might-have-missed-some-steps/

Martin, Aryn, Natasha Myers and Ana Viseu, ‘The Politics of Care in Technoscience’, Social Studies of Science 45.5 (2015), 1-17

Mitchell, David T., with Sharon L. Snyder, The Biopolitics of Disability: Neoliberalism, Ablenationalism, and Peripheral Embodiment (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2015)

Murray, Stuart, Medical Humanities and Disability Studies: In/Discipline (London: Bloomsbury,

2023)

Myers, Natasha, Rendering Life Molecular: Models, Modelers, and Excitable Matter (Durham:

Duke University Press, 2015)

Price, Margaret, Mad at School: Rhetorics of Mental Disability and Academic Life (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2011)

Price, Margaret, ‘The Bodymind Problem and the Possibilities of Pain’, Hypatia 30.1 (2015), 268-84

Schalk, Sami, Bodyminds Reimagined: (Dis)ability, Race, and Gender in Black Women’s Speculative Fiction (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018)

Siebers, Tobin, Disability Theory (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008)

Tomlinson, John, The Culture of Speed: The Coming of Immediacy (London: Sage, 2007)

Tronto, Joan, and Berenice Fisher, ‘Toward a Feminist Theory of Caring’, in Circles of Care: Work and Identity in Women’s Lives, ed. by Emily Abel and Margaret Nelson (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), pp. 36-54

University of Leeds, Disability Equality Framework: https://equality.leeds.ac.uk/governance_strategy_policy/equality-and-inclusion-frameworks/disability-equality-framework-2021/

Viney, Will, Felicity Callard, and Angela Woods, ‘Critical Medical Humanities: Embracing

Entanglement, Taking Risks’ Medical Humanities 41 (2015), 2–7

Weber, Bruce, ‘What is Life? Defining Life in the Context of Emergent Complexity’, Origins of

Life and Evolution of Biospheres 40 (2010), 221–229

Wellcome, What Researchers Think About the Culture They Work In (London: Shift Learning, 2020), https://wellcome.org/reports/what-researchers-think-about-research-culture

Wellcome anti-racism report, https://cms.wellcome.org/sites/default/files/2022-08/Evaluation-of-Wellcome-Anti-Racism-Programme-Final-Evaluation-Report-2022.pdf

Wendell, Susan, The Rejected Body: Feminist Philosophical Reflections on Disability (New York: Routledge, 1996)

Wolf-Meyer, Matthew, ‘What Can We Do with Uncertainty?’ Somatosphere 6 February 2018

http://somatosphere.net/forumpost/what-can-we-do-with-uncertainty/